The Grape Escape: Digital Nomading in Cape Town

A guest essay from South Africa.

Something a little different this week — a guest essay from a former colleague of mine, Geoffrey Lyons, who now lives and works in Cape Town, South Africa. I hope you enjoy!

By Geoffrey Lyons

A few years ago I read The 4-Hour Workweek by Tim Ferriss, a bestseller on how to maximize personal freedom by outsourcing menial tasks and working abroad. While in my opinion the book got too much flak for its “life hack” energy, I agree with its critics that it’s a bit absurd.

The remote work guru himself (Source)

But the absurdity of 4HWW stems not from the book’s bold promises (subtitle: “Escape the 9–5, Live Anywhere, and Join the New Rich”), nor its outlandish advice (Ferriss dedicates a chapter on how to hire cheap personal assistants), but rather its year of publication: it was released in 2007, when virtually no full-time employees had any leverage to negotiate remote work.

Now, in our post-lockdown, hybrid-work world, freedom of movement is negotiable, and many jobs are fully remote by default. In 2021 I was fortunate to land such a job. I was interviewed separately by an American living in Bali, an American living in Brazil, a Fin living in Switzerland, and a Brit who has since uprooted to Portugal. The person vacating the role was a Kiwi living in Vietnam, and then of course there was me: an American living in the UK who would soon move to South Africa. It was as if Ferriss’s dream world, where one could just fuck off to Buenos Aires and learn tango between meetings, had actually come true. But my Buenos Aires would be Cape Town, and in place of tango, my foreign indulgence would be, of all things…

Wine

While South Africa is known as a “New World” wine country, its winegrowing actually dates back hundreds of years, with the first vintage appearing in 1659 (Argentina’s dates all the way back to 1556).

Groot Constantia wine farm (Source)

My first taste of SA wine, not counting some red blends from London supermarkets, was at a beautiful estate called Groot Constantia (“Groot” = “big” in Afrikaans, “Constantia” is a wealthy suburb south of Cape Town), which I would later learn is the country’s oldest wine farm. By 1814, when the British secured possession of the Cape, Constantia’s wine was world-famous, enjoyed by the likes of King Louis-Philippe of France and Napoleon while he was exiled on St. Helena.

One of SA wine’s many fans (Source)

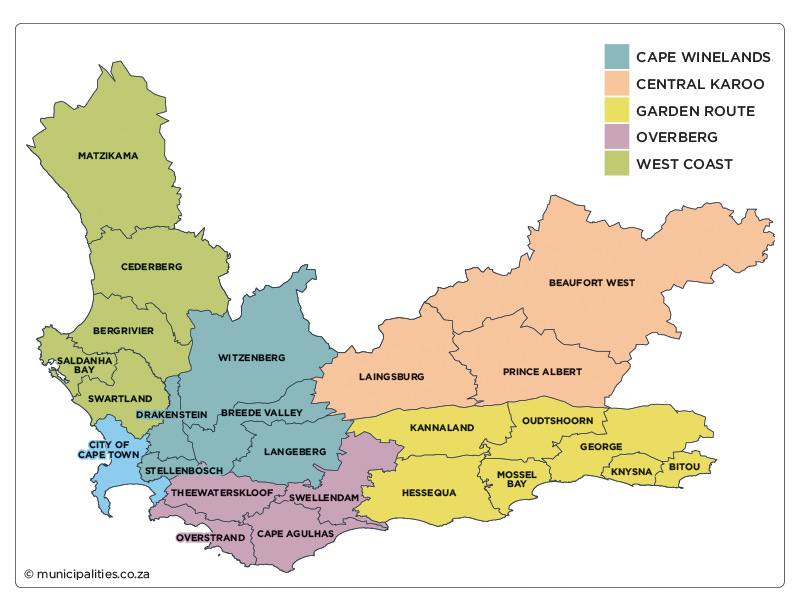

Groot Constantia was a lovely experience, but it wasn’t until I stumbled upon an online debate titled Old World vs New World that my fascination with wine truly blossomed. British wine writer Oz Clark’s masterful and impassioned performance (seriously, give it a listen) compelled me to take advantage of my new home and tour the Cape Winelands. So that’s what I did. I packed a bag and went to Stellenbosch, about an hour east of Cape Town, where a small family vineyard welcomed me into their home. From there I visited the surrounding wine farms and tasted dozens of wines.

Oz Clark swirling a red (Source)

Rather than bore you with the details of my excursion, or what I learned about wine, I’ll simply share the standout features of South African wine farms that I believe make them one of the country’s top attractions:

Luxury: Many estates have chandeliers, grand pianos–the works. They’re beautiful venues worth enjoying in their own right, vino or no. Some, like Steenberg, are luxurious because they’re affixed to a 5-star hotel. Others, like Vergelegen (which has an extensive library of over 4,500 books), were built using money from the Dutch East India Company, a trade empire rich beyond comprehension.

Views: The scenery is breathtaking. As you sip your wine you can feast your eyes on rolling hills, rocky mountains, and a spectacular array of vegetation (of the world’s six floral kingdoms, the Cape is the only one that falls entirely within the borders of one country). There’s often stunning cloud formations, too. Here’s a colourful description of Table Mountain’s “Table Cloth”:

[it] resembles an immense waterfall pouring over the flat-topped summit. Sometimes it is distorted, appearing as a shapeless bank of cloud stacked up over the summit, dark and forbidding; at other times it creeps over the summit edge like a ghostly veil.

Price: By American / British standards, most wine farms are a steal. For R155.00 ($8.50 / £6.70), here’s what you get at Groot Constantia:

Manor House Museum and Cloete Cellar Access

Guided or Self-Guided Cellar Tour (10h00 – 16h00) – hourly

Wine Tasting (five wines of your choice) [Note: SA wine farms pour very generously, sometimes up to half a glass. Befriend the server, and you’re in for a great time.]

Souvenir branded wine glass

Add a chocolate tasting for only R60 [$3]

The fact that I can take a 45-minute Uber for about $5 to one of these gorgeous estates, spend the latter half of a Friday working on my laptop while sipping some of the world’s best wine (purchased, it should be noted, with a 1 USD to 19 ZAR exchange rate) is, to me, what Ferriss must have meant by the “New Rich”.

Closing thoughts

I’ve rambled, I know, but I suppose my overarching point is that Ferriss was right: remote work is a true life hack if there ever was one.

Not only that, it’s more attainable than ever before. COVID pushed many people out of the office and many more about halfway, where they can bargain for the real deal. That means there’s now an alternative to waiting every 6-12 months to ask for a raise / title change, or to move “diagonally” to a better position elsewhere: if there’s a possibility to work remotely, you can give yourself a raise by way of exchange rates (as my American colleague in Brazil put it, “in Rio, you spend and save”). Plus you get a degree of personal freedom you would have otherwise had to work your whole life to attain. What kind of price do you put on that?

But yes, to whoever is reading this, I do realize this may not apply to you. I know that for many professions, remote work isn’t in the cards. If, however, you go into an office two days a week to do the exact same thing you’re doing at home, my question would be: have you asked? I can think of too many examples of people earning much more money for the same work as their colleagues because they asked. In my first job out of uni, everyone was required to be in the office five days a week except for one young woman who worked wherever she pleased because she asked. Recruiters have reached out to me on LinkedIn with vacancies in which I’ve negotiated remote work for slightly less pay because I asked. While applying for a small trade publication in London, I told my interviewer I’d actually like to spend most of my time in the U.S. His eyes lit up. “You could be our US correspondent!”

I got the job but politely declined.

The point is it’s possible. And if nothing’s tying you down to your current location, then I would frame the question like this: is the prize really a $2k pay increase that you’re going to burn on groceries faster than you can say “inflation”? Or is it freedom to roam? If it’s the latter, I raise my glass (of Pinotage) to you.

Geoffrey Lyons is a freelance writer who specialises in finance and cryptocurrency